Reading Ireland 2024: Love Lies A Loss by Theodora Fitzgibbon

Theodora Fitzgibbon is probably best remembered today for her food writing and cookery books, the first of which, Cosmopolitan Cookery in an English Kitchen, was commissioned in 1952. Twenty-five more books (and a novel) followed, including the popular series of 'Taste Ofs' - A Taste of Ireland, A Taste of Paris, A Taste of the Sea (and many more.) I still have her Traditional Scottish Cookery on my shelf today.

And yet Theodora had a much more exciting life than those books might suggest. Like Alice B Toklas, she only started to write them at all to make money. By 1950 her tempestuous marriage to the Irish American writer Constantine Fitzgibbon was falling apart and the couple were living an impecunious, and to some extent profligate, life, largely relying on handouts from their families and many wealthy friends. In 1952 Theodora was already 36. She had previously been an actress and a model, She had been educated partly in Bruges, and had travelled all over the world with her Irish naval officer father Adam, whose hugely influential presence in her life was intermittent to say the least (she once said that as a young child she had only seen him 'maybe half a dozen times.')

She had lived in Paris, where she had an affair with the photographer and surrealist painter Peter Rose Pulham (they remained friends until Peter's early death) and through him had met many painters, including Picasso, Dali, Max Ernst and Cocteau. Back in London she socialised with Francis Bacon and Lucien Freud. But in 1944, as the war dragged on, she met Constantine in a London pub, fell madly in love, married, and for the next sixteen years moved around the world, constantly in pursuit of places to live where Constantine, who considered himself a writer, could write, and they could actually afford to live.

|

| Constantine and Theodora on their wedding day, 1944. Image: Belfast Telegraph. |

|

This may all sound unfairly critical, but the thing I find most taxing about this otherwise well written memoir is that neither Constantine nor Theodora ever seemed to think much about where their next funds were coming from - they just assumed that one of their friends would pay, or that Georgette would send them (as she frequently did) a nice big cheque. The thought of getting a mundane job rarely entered their minds (although one or other of them did occasionally acquire one, usually for a short time until it was all too much...)

|

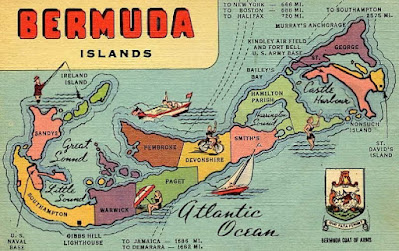

| Bermuda, c 1950- image: RootsWeb |

'why didn't we spend our remaining money on a party?'

Theodora was at one point offered a job, one for which she was utterly unqualified, working in the local newspaper office. Her 'interview' went thus,

'"I think we can fit you in somewhere. Are you married?"...he said that if I was married I must look after my house for some time in the day....so would I like mornings or afternoons?'Turning out to be hopeless at typesetting she was appointed Society Editor, which meant interviewing celebrities who'd arrived on the island. But not for long,

'Georgette said it was too much for me, working and looking after everybody as well....she was contributing very generously to the household expenses...why didn't I give up the job?..With over six hours work, the cooking and sometimes late hours, I was a bit over-tired...'

And predictably, a few weeks later,

'(Constantine) "Mummy's been marvellous. She's advanced my birthday and given me this huge cheque.' ($1,000)"'And so it went on. They decamp to New York, then to Naples, Capri and Rome. Constantine was to write a biography of the writer Norman Douglas, who was by then living on Capri. There they met all manner of people, from two Italian princes and Graham Greene to Gracie Fields herself. They rented a villa, complete with housekeeper ,

'We paid the first month's rent and found that it was just about all we had left.'I suppose people born into this milieu do - or at least did - live like this. To me, the Fitzgibbons' lifestyle is bizarre, irresponsible and immature; they would no doubt have found me boring. They inevitably bumped into some friend or other who was willing to bale them out (on this occasion David Tennant - no not him - and Peter Elder), they saw no issue with asking for credit in the local shops, and indeed felt put out when they didn't get it,

'The once-kindly shopkeepers were very demanding'

'I remembered my father's advice "If you're broke, go to the best hotel. Not only do they never ask you for money until you leave, but you might see someone you know (ie can cadge off)"...Constantine thought it an excellent idea...what a night we had; expensive cocktails...a soufflé, a whole fish grilled with herbs, and excellent wine. We sat on our little balcony with a night cap, saying what a capital idea it had been....The following evening when we ordered our drinks at the bar we were asked to pay for the previous two days....This was certainly something that never arose in my father's time.'The hotel manager tells them they will have to leave and must leave their luggage as surety.

'The next few weeks were very hard.'

Every so often they did get a bit of money from Constantine's publishers - and of course, as soon as they got it, they spent it. The more I read of this book, the more I concluded that people like these are never prepared for adult life. They really do think the world should be pleased to pay for them.

In Rome with her own mother and Constantine's sister, Theodora met Truman Capote and Tennessee Williams. Back on Capri her poor mother was given a very sour welcome by moody Constantine. For some reason she had handed over most of her travel money to him, and when she and Theodora needed cash to go back to Rome, they had first to track him down in a nightclub, whereupon he simply said,

'I have very little money and what I have I need for myself.'The book about Norman Douglas never materialised because Constantine belatedly realised that he couldn't write about Douglas's alleged sexual misdemeanours (he was accused on numerous occasions of pederasty, child rape and indecent assault.)

'Norman Douglas was regarded as one of the smartest things going. Part of that smartness was his keeping, for the whole of his long depraved life, one jump ahead of the law.' (John Sutherland Lives of the Novelists, 2011.)Theodora suggests that people are more liberal in their attitudes to 'sexual misdemeanours' in 1985 (when she is writing the book) than they were in the 1940s. I can't believe that most people would ever have approved of Douglas's behaviour, then, later or indeed now.

So the Fitzgibbons again had no money, and needed to find cheaper lodgings. They - and Douglas - were horrified to find that other people, people not like them, were not only having the nerve to arrive on Capri, but also to rent all the houses and apartments. TOURISTS! Douglas in particular was scathing,

'The island is too small to endure all these outrages without loss of dignity...steamers and motor boats disgorging a rabble of flashy trippers at every hour of the day.'One does wonder if the locals who benefitted from the tourism income would have agreed. But as usual, it's OK to do what you like if you have the right background and accent. Otherwise, please don't.

After sojourns on the Amalfi coast and in Rome, where Theodora was offered some film acting work, and Constantine, back on Capri, stalked her from a distance and raged with jealousy, they eventually settled in Hertfordshire (having at first stayed at a flat in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea - 'The Chelsea flat was fine for a short stay but not for permanent living'), in Sacomb's Ash, a house with seventeen acres. Theodora tells us that the locals were 'a strange folk' (not quite sure what she was expecting in rural Hertfordshire in the 1950s) but they soon found people like them, and of course the obligatory Treasure who did all the housekeeping.

Constantine got worse and worse. He was clearly a serious alcoholic, and unable to cope with his lack of literary success. Alcoholism is of course an illness, but there is less excuse for his serial infidelities, and his increasingly unreasonable and violent treatment of Theodora. She was a loyal and supportive wife, frequently making excuses for her husband,

'There had been precious little laughter over the past year, and I knew it was as much my fault as Constantine's. If your relationship with yourself is honest then, no matter what, your relationship with other people falls into place.'The evidence presented to us here would suggest that, in this marriage, there were far more issues on one side than the other, and whilst we have to accept that the author has only told us what she wants to tell us, to me Constantine comes over as an absolute brute, self-centered, self-deluding and cruel. Any time Theodora was ill, even when she had a miscarriage, he simply left until she recovered, because he 'couldn't bear' illness.

'Constantine had a pathological hatred of sickness, so he always went away at the worst time of my illness, getting my aunt or somebody to look after me and returning when I was better.'Nice.

Eventually even Theodora took time out, and stayed with her own family at Killiney. While there she recalled her convent boarding school in London and her long summer holidays with her cousins in County Clare. I wish there had been more about this, as I think it would've been more interesting than the endless saga of her rather depressing marriage. Wonderful details of life in 1920s Ireland - her train journey from Dublin to Limerick Junction, alone at the age of just 7, but in the care of the guard - as were several dogs, chickens and pigeons; the ponies, the cycle rides, the race meetings, the haymaking, the farmhouse with Virginia creeper growing up the inside walls of a bedroom, because Theodora's aunt 'hadn't the heart to cut it down.'

And on a later visit, being taken to meet a girl called Adza, who turned out to be Theodora's sister, her father having spread himself far and wide. Adza's mother was a singer called Kitty.

|

| Sacomb's Ash today - image themovemarket.com |

And of course, Constantine soon resented her success. His drinking got worse, his affairs became blatant. Theodora visited her mother, who more or less told her that infidelity was inevitable in a long marriage - her main criticism being not that Constantine was having extra-marital relationships, but that he had told Theodora about them. And Theodora agrees,

'To flaunt an affair is an expression of sadistic behaviour...Constant infidelity which isn't felt to be satisfying unless it is boasted about expresses frustration, hostility and resentment.'Quite.

And finally, the inevitable

'On Sunday July 19th 1959....I went back to Ireland, never to return to Sacomb's Ash. This was not entirely my own decision, for someone I had never known had replaced me.'Theodora and Constantine eventually became good friends. He died in 1983. She remarried in 1960 and settled in Dalkey. The marriage was a happy one and lasted until her death at Killiney in 1991. Her husband, the Irish documentary maker (Mise Eire, Saoirse) George Morrison, is now 102 years of age.

I am still not sure what to make of Love Lies A Loss. It's the story of a marriage at times happy, at times miserable. Does it show us how a certain class of people lived in the 1950s? Or does it show us only how these two people lived? The anecdotes about famous people - some still famous, some no longer remembered - are interesting, but in the end I found the Fitzgibbons' lifestyle unattractive. It was as if they both - but most especially Constantine - were forever looking for something they could not find. He, in particular, never really settled to anything anywhere, but always thought a new place, a new book, a new woman, would make life better. Theodora seems to have found much more lasting happiness with her second husband, and it is a shame that no more volumes of autobiography were forthcoming.

'She took hold of life early on, held it firmly by the throat until she died....Her recipes, love of food and lusty approach to the business of good dining were simple extensions of how she lived her life.'*

*Rose Doyle, The Irish Times, 12th April 2014.

Love Lies A Loss by Theodora Fitzgibbon was published by Century Publishing Co Ltd, and also by Pan Books Ltd, in 1985. Second hand copies are available online.

Constantine was my father. He was a brilliant man who struggled with bipolar and alcoholism. I have many happy childhood memories of time spent with Theo and George. In fact I spent my 10th birthday with them while my mother was in the hospital.

ReplyDeleteTheodora was my aunt sadly we never met

ReplyDelete