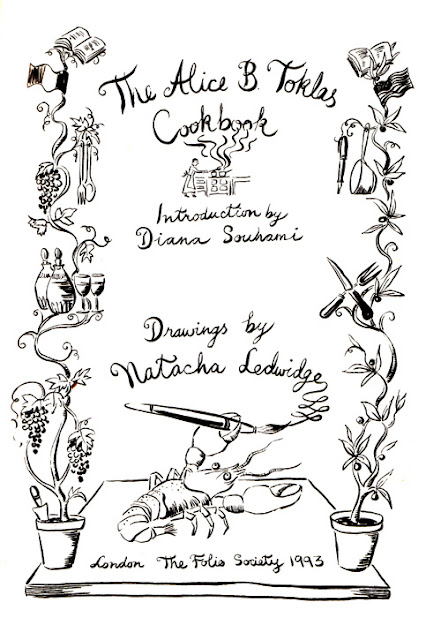

For the #1954Club: The Alice B Toklas Cookbook

In 1907 Alice B Toklas left San Francisco for Paris. Her friend and travelling companion Harriet Levy knew the Stein family, and on 8th September, just one day after they had arrived, she took Alice to visit Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo at their apartment on the Left Bank.

For Alice, meeting Gertrude was a coup de foudre, love at first sight. She heard alarm bells ringing in her head, and knew she was in the presence of genius. The next afternoon she and Gertrude walked in the Luxembourg Gardens and ate cakes and ices at a superlative patisserie. From that day until Gertrude’s death in 1946 they were inseparable.

|

| Alice and Gertrude with their poodle, Basket |

Alice believed, above all, that Stein’s genius must be nurtured and protected.

She did everything for Stein so that Stein could work;

Everything Gertrude wanted, Alice tried to provide….her work of the day was to serve Gertrude. She was secretary, cook, publisher, housekeeper and ministering angel. (Diana Souhami, author of Gertrude and Alice [1991], in her introduction to the Folio edition of the Cookbook)

And this, of course, included all the food. The Alice B

Toklas Cookbook records the numerous wonderful, extravagant meals they ate

(or rather, Gertrude ate, as Toklas herself ate hardly anything), not only in

the Stein apartment on the rue de Fleurus and at their country house at

Bilignin in the Jura (where Alice readily spent an hour at dawn each morning just

picking the strawberries for Gertrude’s breakfast, but told guests to pick

their own) but also in restaurants far and wide, and at the homes of their many

wealthy friends.

Yet the Cookbook did not appear in print until eight

years after Gertrude’s death, and Alice wrote it simply to raise money to pay

her electricity bills (now there's an idea..). Gertrude had left Alice her entire art collection, a bequest

that included work by many of the most important artists of the time, from

Matisse to Braque and Picasso. Alice was free to sell any or all of the paintings, but she

could not bear to – she felt that the collection must be kept intact to honour the

woman she had loved for nearly 40 years. She had mooted the idea of a cookbook

before, but Gertrude had ridiculed her and refused to countenance it; there was

only room for one writer in their relationship, and it was not going to be

Alice. Now that one writer was no more.

At the time of writing her book Alice was actually suffering

from jaundice and having to stick to a very restricted diet – she complained to

friends of ‘bending over an imaginary stove’ and of;

…nostalgia for the old days and old ways and for remembered health and enjoyment (which) lent special lustre to dishes and menus barred from an invalid table, but hovering dream-like in invalid memory.

She wrote the whole thing in just four arduous and ‘tormenting’

months and was not pleased with it when it was finished. She thought it dull.

But whilst this may have been a difficult time for Alice, her book is the polar

opposite of dull; it is instead an unusual and compulsively readable insight

into the lives of two eccentric, determined women and indeed the entire artistic

community in early 20th century Paris. The recipes, fascinating as

they are, are just part of it.

The chapters of the Cookbook are as eccentric in

their titles and content as their writer; Food to which Aunt Pauline and

Lady Godiva led us is all about Stein and Toklas’s adventures in Gertrude’s

succession of cars. (She never learned to reverse ‘She said she would be like

the French army, never have to do such a thing’), Dishes for Artists

records the Tricoloured Bass she invented for Picasso (who was forever on a

diet), while Recipes from Friends features, among contributions from

people like Dora Maar, Francis Rose, Carl van Vechten, his wife Fania Marinoff,

Pierre Balmain and Virgil Thompson, the

notorious recipe (supplied by artist Brian Gysen) for Hashish Fudge (‘it might

provide an entertaining refreshment for a Ladies’ Bridge Club’ wrote Gysen. It

is said that Toklas’s UK publisher, Michael Joseph, had no idea what hashish

was. When Gysen suggested that Gertrude’s experimental writing may have

been drug-fuelled, Alice was shocked and furious.) Another contributor, the poet Mary Oliver, instructs one to;

Place two dozen plucked larks in an oven.

The Murder in the Kitchen chapter, meanwhile, discusses

the necessary executions of fish and fowl and compares this to Stein’s love of crime

stories. Alice’s description of killing a carp brings to mind the famous

lobster scene in Julie and Julia.

While the book is stuffed with recipes, almost every one of which requires colossal

quantities of butter, cream, eggs and alcohol (always ‘the best kirsch’,‘the best white Curacao’ and a panorama of liqueurs, many of which I’d

never heard - Roselio, anyone?), its

real charm lies in Toklas’s memories and anecdotes; almost every dish is placed

in the context of where it was eaten and in what company. Alice and Gertrude knew

everyone in the artistic circles of pre-war Paris; Stein held weekly salons, to

which came Hemingway, Paul Bowles, Scott Fitzgerald and many more. She purchased the works of many emerging artists; there were so many paintings hanging on the

walls that when, at the outbreak of the Second World War, she and Toklas made a lightning visit from

Bilignin to Paris to try to protect them, they discovered that they simply

could not lay them all flat on the floor. (On the same visit they failed to

find their passports, but did unearth the pedigree papers for their pet poodle –

later in the war these enabled him to claim his own rations.)

|

| Toklas and Stein at home in Paris (image: Man Ray) |

At the salons, it was Toklas’s job to provide the sustenance and to entertain the

wives in a separate room, while Stein held forth to the men. The salons

themselves were only set up (by Alice, who else?) because otherwise people kept

dropping in at random and disturbing Gertrude’s work. Now they knew they must

only come round on Saturday evenings. But if all this makes Alice sound like a

doormat, she certainly did not see herself as such;

She was the power behind the throne…The gatekeeper to Gertrude Stein, the promoter of their fame, the shaper of their public image. (Diana Souhami)

In Paris and in the country the two women always (or at

least until the outbreak of the second world war), had a cook. Alice ordered, (sometimes)

shopped and supervised, but her main role was ‘to pass judgement on the finished

dish’ (Souhami.) It would have been

unthinkable for them not to have help. Alice devotes an entire chapter to Servants

in France, their idiosyncrasies, aptitudes and failings. Some stay, some

don’t; one flounces out as soon as she sets eyes on the paintings in the studio

(which Alice has forbidden her to enter.) After the departure of the last of

three Breton sisters, Alice employs their first Chinese cook; her stories of

Trac and his successors are hugely entertaining. When, in 1917, they return to

Paris for just a few days and discover that their cook has left, they resort

to hiring an hourly one. At one point they have a Polish cook, but complain

that her food is ‘too heavy and too rich for a daily diet’ – this from someone

who routinely lobs pounds of butter and pints of cream into every dish.

The recipes themselves are unlikely ever to be attempted by a modern cook – it’s hard to imagine Julia Powell working her way through these coronary-inducing dishes as she did those of Julia Child. Frogs’ Legs with Cream requires 100 frogs’ legs, butter, a cup of hot heavy cream mixed with half a cup of bechamel sauce, another load of butter – and some parsley. For Oeufs Picasso ‘eight eggs and half a pound of butter…rather more if you can bring yourself to it’ – and this was supposed to sit well with the great man’s special diet.

|

| Picasso, Stein and Toklas at Bilignin |

Not only are the recipes rich, they are written in the style of the time, one a

million miles away from that of the 21st century food blogger.

Nothing is organised, little is explained – so, halfway through a recipe,

Alice suddenly tells us that we should have marinated truffles in champagne two days previously. Preparations that should often have been

started days before are thrown in at the last minute; no concessions are

made, and I have to say I find this a refreshing change (to read, if not to follow.) In some

ways Alice’s writing reminds me of Constance Spry, her cookbook being another

of my old favourites.

And although most of the book is firmly rooted in France,

Alice is just as enthusiastic about the food of the USA, and especially her own home state of California. She does not shy way from mentioning the downside of

French cooking – the French, she says, stick rigidly to tradition and countenance

little change, whereas Americans, for all their unfortunate predilections for ready

meals and tins, embrace progress and innovation, and work with some of the

finest produce in the world. Of a visit to the markets in New Orleans she says;

I would have to live in the dream of it for the rest of my life.In 1934/5 Gertrude (but only after Alice had ascertained that the food would be to her lover’s liking) undertook a 7 month lecture tour of the US. Alice naturally accompanied her, making sure that everything was arranged for Gertrude’s comfort, from their crossing on the Champlain (in a stateroom, naturally - ‘we had the best French food’) to their suite at the Algonquin (of course!) While crossing the country they as usual stayed with wealthy, arty, people, all of whom seemed to welcome them with open arms. In other situations we might see this as cadging, but I imagine that Stein and Toklas were such good value as dinner guests that hostesses probably fought over their visits. The chapter about their time in the US could provide enough material for a separate book.

During the First World War the women were keen to do their bit. They drove all

over the south of France for the American Fund for French Wounded, delivering

supplies to hospitals mainly in Paris and the suburbs, and later opening depots at Perpignan and Nimes. And of course they did not stint themselves en route,

staying at good hotels and finding excellent meals wherever they could. Plenty of friends were only too willing to accommodate them, but they did also

spend a lot of their own money on the needs of soldiers and their families.

In the second world war, during the Occupation, the women were in the country. Alice was at

first in despair over rationing and the impossibility of getting much meat –

and most importantly milk, cream and butter;

The flummery cried for cream. So did we.

The vast vegetable gardens at Bilignin - Alice’s domain

and her pride and joy - were a comfort, and at the outbreak of hostilities she had also rushed to

Belley to stock up on hams and cigarettes, just as her father had told her to

do the morning after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. Before very long, however,

the ’blessed black market’ was up and

running, and Alice had no qualms about taking advantage of it – though she was

horrified when a shopkeeper, meaning to be both generous and circumspect, sent

a package of cakes addressed to ‘the two American ladies.’ The French authorities

had done everything they could to keep those ladies’ identities concealed, including

destroying their official papers. For two Jewish women in occupied France,

anonymity was a matter of life or death.

Alice was a chain smoker, and when she ran out of cigarettes

she resorted to

…garden tobacco…we smoked anything we could roll except fig leaves, which had poisoned a friend.

Wonderful post, and you really make me wish I'd got time to revisit the book this week. I don't think it ever would have really functioned as a cookbook, and I certainly wouldn't be doing much with the recipes, but I recall the wonderful memories of Stein.

ReplyDeleteWhat an interesting addition to the club, thanks so much!

ReplyDeleteOhh thank you for the tip about the 2021 edition. I didn't buy the copy in a secondhand bookshop I spotted a number of years back and have regretted it ever since!

ReplyDelete