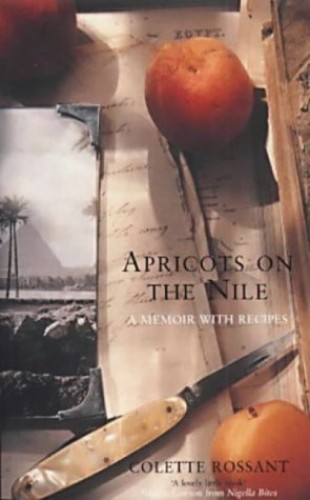

20 Books of Summer: Apricots on the Nile: a Memoir with Recipes by Colette Roussant

This is a memoir about childhood, family, and, especially, food. Banquets, street food, markets, restaurants, but most of all the lavish and delicious meals served every day in the house of Colette Roussant's Egyptian grandparents. Colette arrived in Cairo in 1937. She was five years old. Her story reveals to us a country and a way of life now gone forever.

Colette was the child of an Egyptian father and a glamorous Parisian mother. Both parents came from wealthy families; her father's was Jewish, her mother's Catholic. In marrying his wife, Colette's father had broken a tradition by which all the males in his family sought brides in Turkey; his parents were very unhappy about the match, only partly appeased by this particular bride's huge dowry.

Just two years after the family's arrival in Cairo, Colette's father died. Her mother, always distant and unhappy in Egypt, left Colette in the care of her husband's family and travelled. Colette lived in her grandparents' vast mansion in Garden City, just a block from the Nile, for the next eight years. The house was filled with people - the grandparents lived on the ground floor, an aunt and her family on the first, an uncle with his family on the third;

I don't remember ever eating alone with my parents or grandparents; friends and family members were always dropping by

The family is looked after by an army of maids, a chauffeur and, of course, a cook, Ahmet, a Sudanese (who had a wife and family to support back in his homeland);

Grandmaman was a superb cook. She reigned in the kitchen, but she had to share power with Ahmet.

Before long Colette, who is more or less left to roam the house all day, is spending most of her time with Ahmet (despite Grandmaman's admonitions that a kitchen is no place for une jeune fille de bonne famille) watching him cook, smelling the food, tasting the results, and learning all his skills;

I loved to watch as Ahmet deftly cut the duck's back as it lay flat on the kitchen marble...

For this is a child who loves food, from the ful medames (fava beans) Ahmet makes for the servants, to Grandmaman's special sambusaks, the zalabia ('light, crisp deep-fried dough soaked in honey and orange blossoms') sold by street vendors, 'tiny squabs stuffed with rice and roasted almonds', and Ahmet's kofta served with apricot sauce.

A formal dinner is served every single night - soup, meat course, vegetable course, a salad and dessert.

The table was set with a white damask tablecloth; in the center, two silver birds seemed ready to take off....The cutlery was heavy ornate silver, and the dishes were white porcelain with silver rims....Osman, our servant, dressed in a white galabeyya....with a red sash, was silent as he served.

The rice was fluffy and delicious, but the best part was its bottom layer, which was crisp and golden brown

Ahmet used to make a dish I loved: red lentils, redolent of cumin and garlic and sprinkled with coriander.Colette also loves to visit the many markets of Cairo;

The Khan-al-Khalili open-air market consisted of winding streets and narrow, dark alleys lined with stalls. Streets were named after what was sold on them: Gold Street, Copper and Brass Streets, Silk and Cotton Streets, Carpet Street....the open market was located in a large street, at the end of which was an enclosed fish and poultry market.Here Grandmaman buys okra, tomatoes, courgettes, aubergines, watermelons, pigeons (killed by the vendor after Grandmaman has squeezed their breasts for plumpness), chickens;

My grandmother would insist that the hen be filled with unborn eggs, that the chicken be plump, and that the vendor - brandishing the selected bird by its feet - not kill it in front of me.

Then there is the meat market, which Colette hates - the baby goats, the lambs;

The worst moment was when she stopped to buy slices of beef liver...Two particularly interesting chapters in the book describe Grandmaman's Poker Day, and The Weddings.

For Poker Days, each of eight special female friends have their allocated jour de recevoir; an afternoon of poker or canasta followed by an evening playing high stakes games into the early hours. When it comes to Grandmaman's turn the entire household is turned upside down, first with cleaning and then vast amounts of shopping and cooking, and lastly the donning of all the most valuable family jewellery.

Matchmaking and the weddings that ensued took most of my grandmother's free time. The subject of marriage troubled the older generation.In The Weddings Colette describes the nuptials of many aunts and cousins, including the heartbreaking marrying off of Lucie, who has severe learning difficulties. Poor Lucie is betrothed to one of her father's employees. The results are tragic.

For it is not all sun and sambusaks in Colette's world. Every so often her mother reappears without warning, inevitably criticising her child's weight and her tanned skin; eventually she takes Colette to live with her in an apartment in Cairo, then sends her to a Catholic boarding school run by nuns. Colette hates the place, and of course, what she hates most is the food (Ahmet starts sending her 'care packages' of stuffed vine leaves and cold sweet peppers with cheese and black olives.)

After the war Colette moves with her mother to Paris. Her life in Egypt is over forever.

The final chapter of the book covers Roussant's marriage to an American and their life in New York, where she is delighted to find Syrian and Lebanese food shops. In 1979 she accompanies her husband on a work trip to Tanzania via Cairo. Much has changed - many of the old villas have been replaced with modern high rises, more women cover their heads in public, and they are no longer allowed to bathe with men at the Zamaleck Sporting Club. But some things remain the same;

We ordered squab, tehina, vine leaves, hummus and tomato salad with pickles. The tasty squab were sprinkled with cumin, garlic and lime. We ate them with our fingers and laughed when we looked at our plates. Virtually no bones were left; we had chewed on everythingApricots on the Nile perfectly captures a time, a place and a way of life, but Roussant does not sugar-coat her childhood. She was privileged, but she was also lonely and insecure. Her descriptions of the important people in her life - her grandparents, her aunts and uncles, and most of all their servants - bring this book to life; we can hear Grandmaman and Ahmet in the kitchen, arguing and laughing, see the horse-drawn carriage on its way to the market, and most of all we can smell the tantalising aromas coming from that wonderful kitchen, the place little Colette always felt most at home.

|

| Colette Roussant: image: simonandschuster.com |

Apricots on the Nile by Colette Roussant is published by Bloomsbury.

Comments

Post a Comment