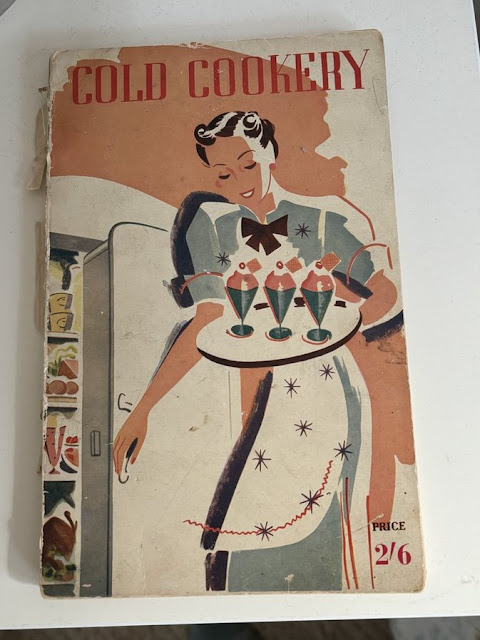

For the 1937 Club: Cold Cookery by Helen Simpson

I was going to review another Golden Age mystery for my third contribution to the 1937 Club, but I didn't like the one I read very much, so my attention was caught by a little booklet that I had dug out when I first started thinking about books for April's reading week. It turned out to be a lot more fun - and interesting too.

COLD COOKERY was published by The British Electrical Development Association of Savoy Hill, WC2. In those days such organisations really did have their offices on some of the capital's most exclusive streets - Savoy Hill seems to be just behind the hotel itself.

The purpose of the booklet is to persuade people - mainly women, here unashamedly referred to as housewives - to invest in a fridge. It seems to be aimed at 'normal' families, which I find quite interesting in itself - did people really have domestic fridges in those days? My own parents married in 1952 and all they had was a 'food safe' - a sort of wooden cupboard with a wire grill - that was kept in their landlady's garden. I don't think they acquired a fridge for another few years, probably when they bought their first house. And as for a freezer - mentioned briefly here - I don't think my mother ever had one, yet I can't imagine managing without mine.

The introductory paragraph of Cold Cookery, written by Helen Simpson, 'well known novelist and author', begins with a reference to Francis Bacon, Lord Chancellor of England in 1618. I really can't see any cookery book, least of all one designed to instruct rather then entertain, opening with anything like that today. But here is Ms Simpson, confidently assuming that her readers will know of what she speaks. She tells us that Bacon once went out to collect snow to stuff a chicken, believing that cold was a preservative against decay,

'Nowadays snow is at hand even in summer, and we prove Bacon's theory every day without risk to ourselves; those of us, that is to say, who own an electric refrigerator. It is tame snow, but dependable. You can do everything with it except ski. It knows its place. It is snow with work to do.'There then follow several pages of reasons why everyone should have a fridge - they're really quite technical at times, and on the whole their facts would still stand up, though I think it'd be a brave vendor now who would confidently announce,

'Once you have installed one in your home the danger of contaminated food is ended.'I can hear a million insurance brokers having an attack of the vapours at the mere thought of such a potentially litigious statement.

(We are also assured that flies can't get into fridges - so presumably the door is never opened...)

The writer has a big down on cellars as a place of food storage,

'Where is the cellar that has not a damp spot somewhere?'Well I grew up in a house with three coal cellars, and I remember my parents storing all sorts of things down there. We survived. Similarly, although we did by then have a small Electrolux fridge, leftovers, blancmanges (I feel a Barbara Pym moment coming on...all those 'shapes' on the sideboard..) and cheese were all kept in the pantry. Nowadays only people like Nigella have larders; for most of us space is at a premium - but the reason we didn't succumb to all the awful illnesses threatened in this book is no doubt because our houses were freezing. And no I am not in the least nostalgic for those pre-central heating days, but I honestly think not much needed to go in a fridge in the 1960s.

An ominous section is headed The Growth of Bacteria,

'If flies, dust and mould are dangerous to food, how much more dangerous must bacteria be?'

If you weren't worried before you read Cold Cookery, you would be now....but fear not,

'(A refrigerator) works quietly, consistently, guarding your health day and night....it aids entertaining, beauty and economy, and contributes in an amazing way to the housewife's peace of mind.'In a section headed Why The Electric Refrigerator is Best, the housewife - who clearly has many, many worries with which to contend - is informed that she,

'need not be afraid that the introduction of an electric refrigerator into the house means spoilt radio or television programmes, as modern refrigerators do not cause interference with radio reception.'There were only about 20,000 TV sets in domestic homes before the Second World War, but you wouldn't have wanted your fridge to interrupt the National Anthem!

The housewife's family, we are told, will be newly delighted to see leftovers reappearing at the dinner table,

'A dish can be re-served having lost none of its vitality or freshness, and moreover can often be transformed into a tasty souffle or mousse.'So much for saving you time then, you'll be busy knocking up all those souffles - and if you need assistance, the second part of the booklet is full of recipes with names like Salmon Jelly (to be served with a garnish of yellow turnip 'lilies')

There's a section on Invalid Cookery too, and my goodness you'd want to recover quickly if faced with a diet of milk jelly, egg jelly, calves' foot jelly and 'egg pick-me-up'... And if you want (of course you do) to know how to make 'cream' from evaporated milk, just turn to page 34...

And of course, the housewife will be mightily relieved by this little nugget of information,

'The man of the house, of course, will most probably want his siphon or his beer served at the right temperature, so that a little space must be put aside for this...'Even when my children were small and our large fridge was always overflowing, we kept the beer in the shed at the bottom of the garden. It gave a new meaning to 'I'm going for a short walk...'

Yet at the very same time as British houses were living on such unappetising food, across the channel in Paris, and in Bilignin, Alice B Toklas was dishing up all manner of wonderful meals to please Gertrude Stein. Butter, cream, wine and eggs flowed freely, liqueurs were poured into pans with abandon. While you may say that Alice and Gertrude were hardly, at that time, short of money, I'm sure even the humblest French kitchen would never have been home to a mould, much less a floating island salad.

When Gertrude is considering the possibility of a lecture tour in the US, she is deeply troubled about what the food will be like back in her home country. A friend who has just returned from a visit there reports that

'the food was very strange indeed - tinned vegetable cocktails and tinned fruit salads, for example. Surely, I said, you weren't required to eat them?'(In fact the women ate very well in places as diverse as New York, New Orleans, Chicago, Dallas, Austen, Pasadena and Monterey - goodness only knows what they would have made of the menus in the UK.)

|

| Alice B Toklas and Gertrude Stein at home in the Rue de Fleurus, image: Man Ray |

Today cookery programmes abound, cookery books fill bookshop shelves, and Jamie Oliver, Nigella, Nigel Slater. Rick Stein and Heston Blumenthal exort us to experiment. But do we? I have no idea. As someone who rarely cooks more than a boiled egg, I am certainly not taking the moral high ground here, but I do wonder if we are simply a nation not that much interested in food.

Whenever I have visited a French market I have been struck by how high a proportion of their likely incomes French people are prepared to spend on meat, fish, gateaux for Sunday lunch, butter, cheese and all the fabulous produce available to them. Whilst we have farmers' markets now, they are considered expensive and largely the preserve of the monied middle classes. Ready meals and Deliveroo take aways are hugely popular - and probably sometimes eaten in front of Masterchef or the Bake Off.

I will leave you with one more worrying Cold Cookery paragraph. On page 33 are the mystifying words 'Ice for the Toilet' - but before your imagination runs riot (my daughter said 'it reminds me of baths full of ice for student parties - but in the toilet?') let me reassure you that Ms Simpson is merely keen to inform us that,

'ice is of great use in an emergency for medical use, as, for example, in cases of haemorrhage...the cold pack is of great use also in relieving headaches...in the same way ice can be used for the toilet after shaving, etc.'Food and cooking are such interesting indicators of a society's values and customs. I find old cookery books fascinating, and Cold Cookery is no exception.

I think of cookbooks as a form of armchair travel because in real life there is almost always some ingredient I dislike, and there are just a few recipes I can make well and relatively quickly. However, I tried to work recently with two shops that opened a few years ago, specializing in selling items about to expire. One is across from my office and as my organization provides personal finance training for low income residents, I thought maybe we could offer workshops to the staff or shoppers of these shops, both of which are in poor neighborhoods. They were also planning to offer free cooking lessons to focus on fresh vegetables and other healthy items. However, the items that sell best are prepared foods, which aren't that inexpensive. The cooking classes didn't last and no one showed up for my credit building workshop, alas!

ReplyDeleteGosh what a wonderful book and a fascinating piece of social history. I love old cookbooks too, they're a window into the past and as you point out, really do reveal the dire state of British cooking at the time. Even ones I have myself from as far back as the 1970s are pretty weird in places. Thanks for reading this - brilliant!

ReplyDeleteWhat a brilliant addition to the 1937 Club! I'm converted; I'll be getting a fridge asap :D

ReplyDelete